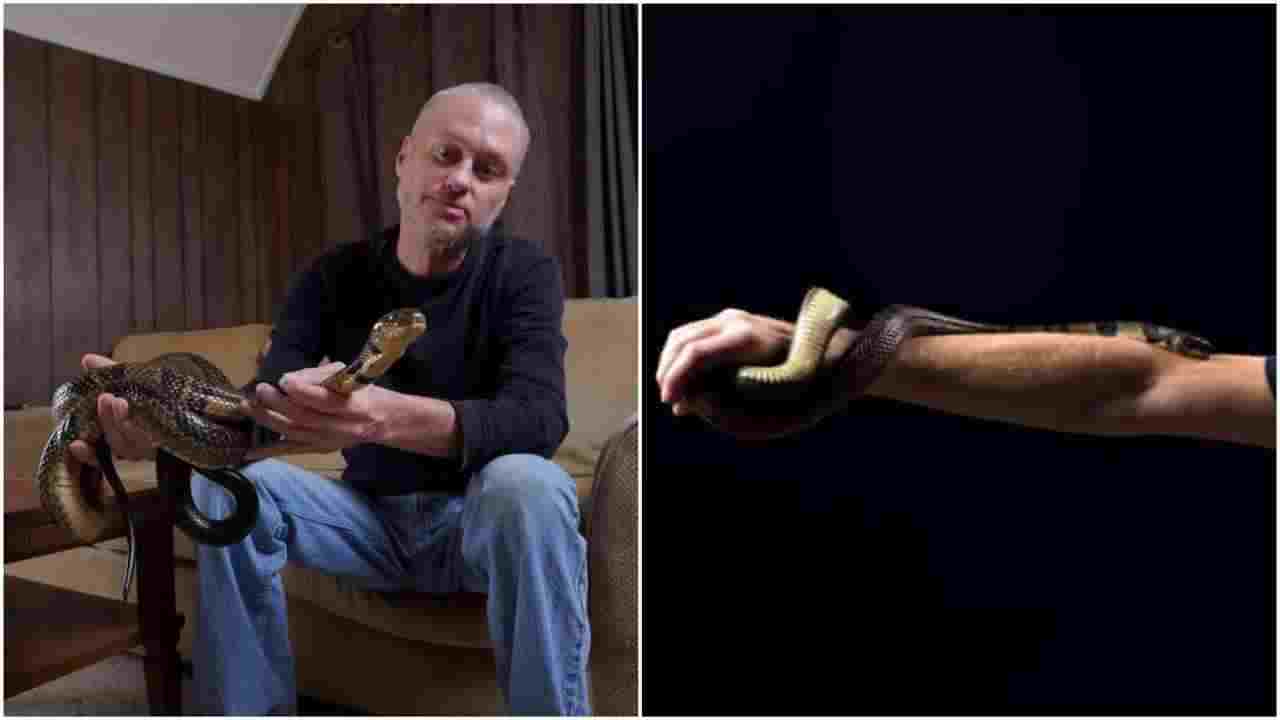

When most people hear about someone voluntarily getting bitten by deadly snakes over 200 times and injecting snake venom into their body more than 700 times, they would probably call that person insane. But Tim Friede, a man from the United States, has done exactly that—intentionally risking his life again and again in the name of science. His goal? To develop immunity against venomous snake bites and pave the way for a universal antivenom that could save thousands of lives around the world.

The Mission Behind the Madness Of Tim Friede

At first glance, Tim Friede’s mission seems suicidal. Who in their right mind would repeatedly expose themselves to venom from some of the deadliest snakes on the planet—including the black mamba, cobras, kraits, and others? But according to Tim, there’s a very clear reason behind his extreme actions. He wants to help create a universal antivenom—one that works across multiple snake species—and he’s using himself as a live testing ground to prove it’s possible.

Friede’s logic is based on a simple principle: if the human immune system can be trained to fight off snake venom, then we could create better, broader antivenoms that would work in emergency situations without needing species-specific serums. Currently, most antivenoms are developed by injecting venom into animals like horses in small amounts until their immune systems produce antibodies. These antibodies are then harvested and purified for human use.

But there’s a problem with that method—it’s species-specific. Antivenom for one type of cobra won’t work on another cobra species, let alone a black mamba. In regions where multiple venomous snakes coexist, this poses a serious risk to human lives because identifying the right antivenom in time is not always possible. That’s where Tim Friede’s mission becomes groundbreaking.

The Dangerous Road to Immunity Of Tim Friede

Tim Friede has been working on his immunity project for over 20 years. Over this time, he has injected himself with diluted snake venom more than 700 times and voluntarily allowed himself to be bitten by some of the most dangerous snakes alive—over 200 times. He’s been bitten twice by a cobra, which nearly killed him. After barely surviving that incident, he didn’t quit. Instead, he doubled down, studying how his immune system responded and continuing his self-immunization experiments.

Each injection and bite was meticulously recorded. Over the years, he developed resistance to multiple snake venoms—an achievement once thought to be impossible. According to scientists who studied his case, Friede has successfully developed antibodies in his bloodstream that neutralize the toxins from at least ten venomous snake species.

These results amazed researchers. Normally, someone bitten by a venomous snake has a 50/50 chance of survival if they don’t receive immediate medical attention. But Tim Friede defied those odds—repeatedly. His blood has now become a key resource in the quest to develop a more universal snakebite therapy.

How Does Antivenom Work—and What Makes Tim’s Blood Special?

Traditionally, antivenom is produced by injecting small doses of venom into animals like horses or sheep. Over time, these animals develop antibodies against the venom. Scientists then collect and refine those antibodies into a serum that can be administered to snakebite victims. However, the catch is that this process only produces antivenom specific to that type of venom. For example, antivenom made using Indian cobra venom will not work for a bite from a black mamba.

This specificity is a major issue in remote or rural areas, especially in tropical countries where multiple venomous snake species are present. Many victims don’t receive the right antivenom in time—or any antivenom at all—leading to death or permanent disability. Every year, over 150,000 people die globally due to snake bites, and hundreds of thousands more suffer amputations and life-altering complications.

Tim Friede believes that by building his own immunity to multiple snake venoms, he can help researchers study how a human body can produce broadly effective antibodies. His blood has already proven valuable to scientific teams, who are now exploring the possibility of creating a “cocktail” antivenom that could neutralize multiple types of venom in one shot.

Scientists Begin Research Using Tim Friede’s Blood

A team of researchers recently analyzed Tim Friede’s blood, looking for broadly neutralizing antibodies. The study, published in the journal Cell, focused on the Elapidae family of snakes, which includes some of the most dangerous species in the world: cobras, coral snakes, taipans, kraits, and black mambas.

Elapids typically use neurotoxins in their venom, which affect the nervous system, leading to paralysis and eventually death by respiratory failure. Researchers chose 19 elapid species identified by the World Health Organization as among the deadliest and searched Friede’s blood for antibodies that could fight their venoms.

Remarkably, they discovered two powerful antibodies that could neutralize two distinct classes of neurotoxins. They then combined those antibodies with a third drug that targets another toxin type. The result? A powerful antivenom cocktail that, when tested on mice, enabled them to survive lethal doses from 13 out of the 19 snake species. For the remaining six species, the cocktail offered partial protection.

Toward a Global Antivenom

This is a major step forward in snakebite treatment. Instead of needing a separate antivenom for each species, future treatments could rely on a single broad-spectrum antivenom. While this idea is still in development and human testing remains years away, Friede’s contribution has opened new doors for researchers.

Dr. Jacob Glanville, an immunologist who co-led the study, told media that Tim Friede’s unique biology provided a real-world case of “multi-species immunity” that had never been studied in such depth. The potential to develop a global antivenom could dramatically change how we deal with snakebite emergencies in underdeveloped regions.

Motivation Behind Tim Friede’s Efforts

In Tim Friede’s own words, “It just became a lifestyle and I just kept pushing and pushing and pushing as hard as I could push—for the people who are 8,000 miles away from me who die from snakebite.” He’s not in it for fame or money. In fact, much of his work has been done in private, in his own home laboratory, with minimal institutional support.

His motivation comes from knowing how many lives are lost each year due to lack of proper treatment. He’s seen stories of children and farmers dying from preventable snakebites simply because they didn’t receive the right antivenom in time. That sense of injustice drives him to keep going, despite the enormous risks to his health.

Public Reaction and Controversy

Unsurprisingly, Friede’s mission has received mixed reactions. While many scientists and medical professionals admire his courage and contributions, others are concerned about the ethics and safety of self-experimentation. Social media has been flooded with videos of Friede getting bitten or injecting venom, leading some to call him reckless or even mentally unstable.

But regardless of the criticism, his work has proven invaluable. His blood has become a goldmine of immunological data. His sacrifice might one day lead to a cure that saves countless lives.

A Lifesaving Legacy in the Making

While we are still several years away from a commercially available universal antivenom, the progress made thanks to Tim Friede’s work is undeniable. Researchers are now more hopeful than ever that such a treatment can become reality—potentially saving over 100,000 lives each year and offering hope to regions of the world where snakebite deaths are common and tragic.

The work being done on Tim’s blood is ongoing. More research is required to refine the cocktail of antibodies and ensure it works safely in humans. But the fact that one man’s extreme commitment to science could have such a massive global impact is a powerful reminder of how far some people will go to make the world a better place.

Conclusion

Tim Friede may not wear a lab coat or work in a high-tech laboratory, but his contributions to medical science are remarkable. He has turned his body into a living experiment, repeatedly enduring pain and risking death to fight a problem that takes more lives than many realize. If the scientists studying his blood succeed in creating a global antivenom, Friede’s name may be remembered as one of the unsung heroes in the fight against snakebite fatalities.

Until then, he continues his mission—one injection, one bite, and one antibody at a time.